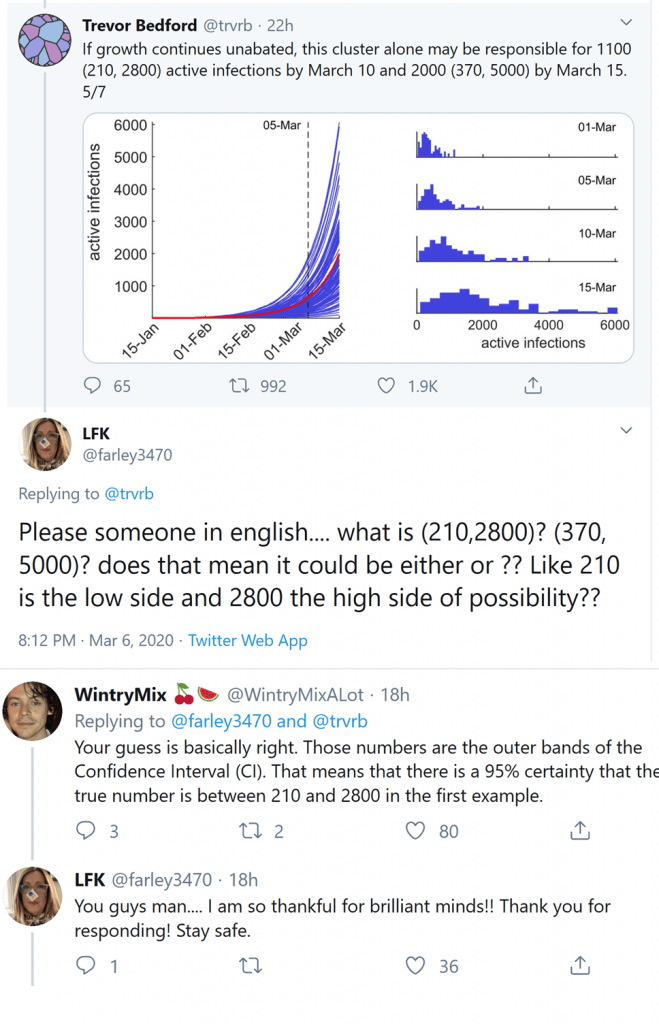

Coronavirus news is dominating our mental and physical airwaves – I for one have eyes glued to virologists’ Twitter feeds and am constantly refreshing the Seattle Times daily updates. Scrolling through tweets the other night (I have self-diagnosed “Scrolliosis”), I saw a fascinating exchange in the comments. My favorite computational biologist, since that’s a thing we have now, was posting some coronavirus stats when a commenter asked for someone, “in English please,” to explain the way he was presenting the numbers:

The commenter’s hunch was basically right, but someone jumped in to confirm – the numbers in parentheses are the 95% confidence interval, meaning there’s a 95% chance that the true estimate lies between those numbers (sorry statisticians, I’m surely missing some nuance about sampling, but heuristically – this seems a reasonable way to think about it). Given that social media can be a vicious and petty place, I was genuinely touched to see this honest and helpful exchange, demystifying a small bit of statistical jargon in the context of an urgent and critical public health topic.

Drawing boundaries around scientific expertise

Like many recovering PhD students, I filter most experiences and information through the lens of my dissertation topic. I studied how people use online interpretation tools to try and make sense of their “raw”/uninterpreted genetic data from direct-to-consumer testing companies such as 23andMe and AncestryDNA. (I’ve written more elsewhere about interpretation tools and their users.) What many of these tools do is leverage (or co-opt, depending on your point of view), publicly available sources of information about genetic variants, such as annotation and literature databases. These sources are public for a variety of reasons, including the principle that taxpayers should have access to the fruits of publicly funded research and also the idea that, for science to advance, researchers need to be able to easily share and access each other’s work.

So, how great that tools enable non-specialists to overlay all that knowledge onto their own genomes and try to glean some personal insights, right? Well, many genetics professionals (researchers and clinicians, e.g.) understandably cringe at these interpretation tools and at direct-to-consumer genetic testing more generally. It feels premature and perhaps a little exploitative (of both the science and the customers) to try and translate an evolving science into personal insights. At the same time, trying to shut it down completely smacks of paternalism and seems an unfair denial of information about one’s own, very personal, genome. To add, it’s a bit too late. Over 26 million individuals have taken a direct-to-consumer genetic test and my research indicates that a majority of them have further downloaded their data and plugged it into a online tool. Legal scholar Barbara Evans has described the demand for personal data access and its use in research as “barbarians at the gate” — and today I’d say, the castle has already been stormed.

The question boils down to: Who gets to interpret their own genome, and with what resources?

Knowledge infrastructures as community spaces

Knowledge infrastructures are “robust networks of people, artifacts, and institutions that generate, share, and maintain specific knowledge about the human and natural worlds.” The internet and social media have shaken up historical ways of sharing knowledge, like seismic activity below the surface of our traditional academic and government institutions (it’s not a perfect metaphor, but none are). Watching coronavirus information (and sadly, misinformation) spread is a good example, and the micro interaction on Twitter I described above an even more perfect example. A professional is giving real-time, robust information on a public health crisis, and members of the public are engaging with the information and asking questions. In this example, the interactions led to a better, shared understanding of the situation at hand. It’s good that us barbarians are at the gates, demanding to know more from experts and increasing our shared understanding. We in turn should be grateful that people have devoted their careers and lives towards specialties that were previously hidden, or at least not well appreciated.

Opening up the gates of genetic information is maybe not as urgent or immediately impactful as for the coronavirus (granted, there are exceptions for some types of genetic risk). However, I am thinking about potential lessons learned about sharing of professionalized knowledge, of treating these “knowledge infrastructures” like public spaces – the libraries and parks of information. It requires public support and mutual, intellectual respect, along with a recognition that science, and scientists, are not infallible. Research is iterative and there are confidence intervals around pretty much everything. But if we can share and explain that uncertainty, engaging in it together, wouldn’t that be something?