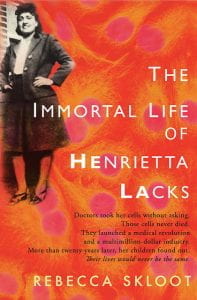

In October, my graduate program hosted a public screening of “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks,” followed by an expert panel discussion. For those unfamiliar with Rebecca Skloot’s book and the story of HeLa cells, I highly recommend these two Radiolab episodes as background. Briefly, Lacks was an African-American woman diagnosed with cervical cancer in Baltimore during the 1950’s. A sample of her tumor cells taken during her time in Johns Hopkins hospital ended up being the first time scientists were able to grow living, human cells in the lab — something they’d been desperately trying to do for quite a while. Her cell line was called “HeLa” and basically kickstarted modern biomedicine.

One of the many things I appreciated about the expert panel discussion (a full recording of which is available on YouTube) was how it helped to parse and sort various issues raised by Henrietta Lacks’ story. Watching the movie, you viscerally get a sense of multiple lines of injustice, of anguish, by Lacks herself and by her descendants and in particular her daughter, Deborah (played by Oprah). There’s the abundant racism, the absence of informed consent, the financial injustice of a wildly profitable biotech industry enabled by the unwitting donation of a poor black woman. Taking this story in, all your protests can easily get muddled up into one ball of outrage. But, as the panelists that night helped me see, it’s helpful to pick it apart a little. In doing so, you come to realize that perhaps the most unjust aspects of this story are not the extraordinary details but the rather ordinary backdrop of systemic racism.

Informed consent

One major theme in this story is the lack (no pun intended) of informed consent. Lacks was never asked (or even told) about her tumor cells being used for research. Furthermore, when her family members were later brought in for genetic testing — an opportunity for the researcher-clinicians to come clean — the family was actively misled. They were told it was for their own benefit (to detect cancer risk), rather than the real reason of wanting genetically-related samples to help detect HeLa cells in the lab.

This issue is a little thorny, even by today’s standards of biomedical research ethics, some of which were not even codified until the 1960’s. “Biobanking” is a fairly common practice now, especially in healthcare systems tied to research institutions. Biological samples collected for different purposes, sometimes clinical treatment (e.g., tumor biopsies), get stored and potentially used for various downstream research projects. The samples are typically de-identified and therefore subject to a laxer form of regulatory oversight. As Dr. Wylie Burke mentioned on the panel, ideally such systems make patients aware of the biobank and at least give them an opt-out option — neither of which applied to Henrietta’s tissue “donation.”

Profit sharing

Another objection that comes up when watching or reading the HeLa story is that of profit sharing. The HeLa cell line, while initially given away freely by Johns Hopkins researchers, eventually became a massive revenue generator for numerous biotech companies. Yet the Lacks family, to this day, remains socio-economically depressed. While certainly unfair, by current legal standards I think it’s unlikely the Lacks family would be granted a share of the biotech companies’ profits — potential ethical obligations aside. A 1990 legal case sets a precedent here, Moore v. Regents of the University of California. Cells taken from a cancer patient, John Moore, became a cell line patented for commercial use. Moore sued and lost, the court ruling basically that Moore did not have a financial interest in the cells once excised from his body. (Note, this case also involved issues of informed consent, which of course was breached in the case of HeLa cell line creation.) The legal precedent of no property rights in excised cells/tissues was held up in 2003, in Greenberg v. Miami Children’s Hospital Research Institute. An important caveat with comparing HeLa to this case is, again, that in Greenberg the court was considering a scenario where tissue samples were freely donated by patients, i.e. with proper informed consent.

Structural racism

The circumstances I’ve covered so far are indisputably concerning, but what if they’re distracting us from a greater injustice? This was the possibility raised to me by the expert panel after the screening that night, and in particular the renowned bioethicist Dr. Wylie Burke. What if the real whammy here, crystallized in this one extraordinary story, is the background of structural and institutional racism? This is different than the specific question of financial interests in the previous section. This is about a history of underprivilege and lack of access to educational, employment, and health resources.

One specific example was brought up by the panel moderator and former Dean of the School of Public Health, Dr. Gil Omenn. Henrietta went through two pregnancies likely with this tumor on her cervix — why did her health care providers not catch this? It was only once the tumor was advanced enough that Henrietta could feel it herself that she began to receive treatment. We can’t say for sure, but it seems likely that her standard of care was inadequate. You also see the system continue to fail for Henrietta Lacks’ living family members, many of whom suffer chronic physical and mental illnesses. These background injustices would be no less salient even if Henrietta Lacks’ cancer cells had not gone on to fuel a biotechnological revolution. It’s because her cells were so extraordinary, and because Skloot was so stubborn about accessing the family and this story for her book, that we get to and should talk about these underlying injustices.